Click here to return to Roman civilisation menu

Click here for main Classics menu

If you have enjoyed reading these notes, please click hereand visit this site for info on Paul andrews' novel, the Loner.

The Roman Republic

Rome was a city state founded in about 753 BC.

500 years later Rome controlled Italy. The other Italian cities were bound to Rome by a military alliance. The terms of this allowed Rome to levy troops from them to fight Rome's

wars. The Roman word for a levy was "Iegio", and this is how the Roman "legions" came into

being.

In most other respects the Italian cities kept their independence, paying Rome no taxes.

Then Rome expanded her influence outside Italy, and Rome and her Italian allies conquered Sicily, Sardinia and Southern Spain. Instead of making the cities in these lands her allies, Rome grouped them together into provinces, appointed governors and made them pay taxes to Rome.

Eventually, Rome's empire controlled most of the Mediterranean coast, and this created

political and social problems. Although Rome was a republic with strong democratic traditions, no citizen could vote unless they were in Rome during elections. A small town Council in effect ruled the world, and the world was too big for it.

There were coups, counter-coups, revolutions and civil wars, and eventually the military took over. The Roman word for "Commander in Chief" is "imperator", and constitutionally the Roman emperor was more what we would describe as a "president" than a hereditary monarch. In theory the emperor had to be appointed by the Roman Senate. In practice, they tried to keep the job in the family and there were a series of short-lived dynasties.

Right to the very end, Rome was, in name and in legal theory, a republic.

Politics in the Republic

There were no organised political parties in the sense we now know. However, in the early days, the ordinary people sometimes insisted on their rights by withdrawing their support for the state - a process rather like going on strike.

In the later Republic, there were at least two political factions which had their own distinctive names:

The "Optimates" - the party which supported the aristocracy;

The "Populares" - a kind of "Peoples'" party which had for its

agenda a limited redistribution of wealth, so as to make available unused land owned by the aristocracy for farming by poorer citizens, and the provision of free corn and free

entertainment ("bread and circuses") to the citizens of Rome.

Some Famous Romans

Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43BC)

Sounds a grand name, but "Cicero" is the Roman word for a chick pea. So his name was more like "Mark Smith"! Scholars in the18th century could never accept this: so they called him "Tully" instead.

He was a lawyer and became the leading Roman barrister.

He entered politics and tried to steer a middle course between the Optimates and the Peoples' party.

Up to 66BC the Eastern Mediterranean was infested with pirates who operated from the South of what is now Turkey - rather like nowadays pirates are based in the Horn of Africa.

Cicero proposed a law which authorised Pompey, a Roman general to clear the seas of pirates. Pompey did this in three months - quite an achievement in days of sail and horse

and cart. Now, we could do with somebody like Pompey to clear the pirates from the Horn of Africa!

In 64 BCCicero became Consul (the highest office of state) and successfully prevented a coup by a dissolute aristocrat

called Catiline.

He led a determined campaign to save the Republic after Julius Caesar's death, making speeches and writing pamphlets against Julius Caesar's former deputy, Mark Antony.

Eventually Antony made an alliance with Caesar's nephew, Octavian. They set up a military junta and defeated the republicans. Antony's men murdered Cicero on 7the December

43BC.

Cicero was a prolific writer of legal and political speeches, letters and philosophical treatises. His style would have appealed to what we might call a "Guardian" reader.

Some of his best legal speeches read like thrillers.

Murder at Larinum - a Roman thriller by Cicero

.

Cicero was instructed to represent Cluentius who was being prosecuted for the poisoning of his step-father Oppianicus. This is the story told in Cicero's speech for the defence.

Oppianicus, a citizen of Larinum, is portrayed as a heinous money grabbing villain. He

murdered his brother in law and a witness to that murder, to get hold of his step-mother's estate.

Oppianicus then courted Cluentius' mother, Sassia.She refused to marry him, as he had two sons. So Oppianicus murdered his two children and married her. The paternal aunt of

Cluentius was Oppianicus' ex-wife. Oppianicus killed her, and with the same poison, his own brother. His brother's wife was pregnant. Oppianicus poisoned her before she could bear

and inherit. Oppianicus' uncle left everything in his will to the son of whom his sister was pregnant. Oppianicus who was next in line in succession paid her a large sum, and she

aborts.

Oppianicus was eventually prosecuted and convicted for the attempted murder of somebody else.

Eight years later Oppianicus was himself poisoned and Cicero's client, Cluentius was prosecuted for his murder.

One of the issues at the trial was an allegation that Cluentius had bribed the jury to convict Oppianicus in the trial eight years before. Cicero admits that there had been bribery:

Oppianicus had tried to bribe the 32 jurors, but this backfired. He had paid the full bribe to one of the jurors, who double-crossed him and used part of the money to get him convicted instead.

Cluentius was acquitted, but who was the real murderer of Oppianicus?

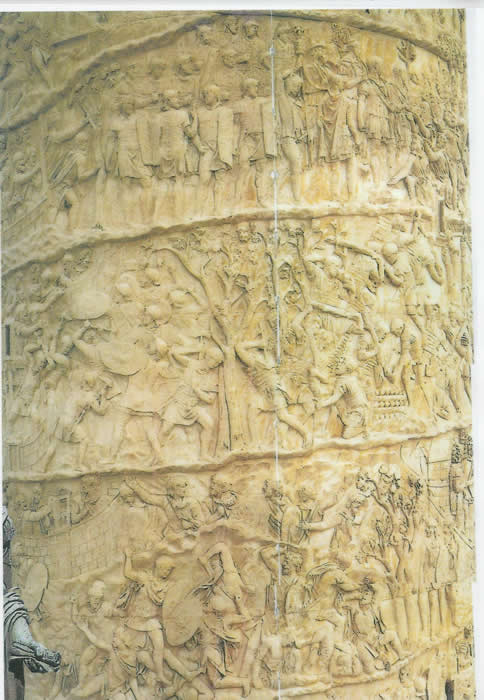

Roman soldiers from Trajan's Column

Julius Caesar (102 - 44 BC)

An aristocrat by birth, his family was connected to the Peoples' Party, which he led for most of his life.

He was Consul in 59BC(one of two equally powerful heads of state), and in 58BC was made

governor of three small provinces in North Italy and Southern France. Between then and

49BC he commanded the army which conquered France (then called Gaul) and invaded

Britain.

His invasion of Britain failed.

He wrote a commentary on the Gallic War in a simple style which was designed to appeal to

what we would call "Daily Mail" readers, and this was partly designed to promote himself

politically as a successful patriotic general. His commentaries do not acknowledge his British

expedition was a failure!

In 49BC he was recalled to Rome. Suspecting treachery, he took his army back with him and

fought and won a bloody civil war against the Republic's armies, staying for a while with Queen Cleopatra of Egypt, with whom he had a son.

He reformed the calendar: the month of July is named after him.

He was assassinated by republicans on the Ides of March 44BC.

.

Mark Antony was his cavalry commander and deputy.

After Caesar's death, Antony and Caesar's nephew, Octavian, formed a military junta with another man called Lepidus, and there was another civil war against republican armies led

by Caesar's assassins.

All the Roman emperors called themselves "Caesar", and the title was later given to the German "Kaiser" and the Russian "Czar",

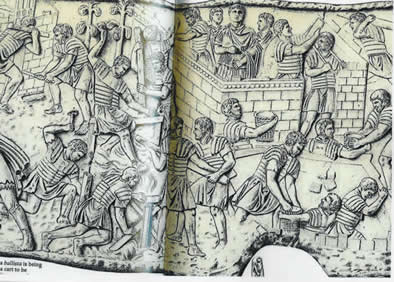

Roman soldiers building a camp - Trajan's column

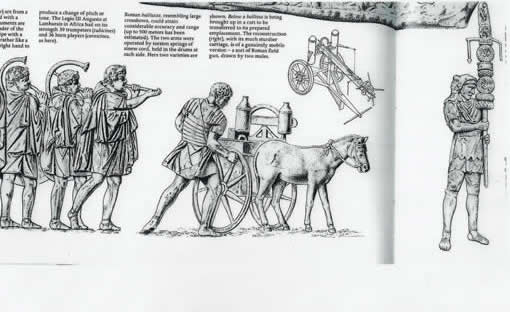

Trumpeters, artillery and standard bearer from Trajan's column

Octavian Caesar - the first emperor (63 BC - AD 14)

Octavian was Julius Caesar's nephew. He was well educated and highly intelligent.

After Julius Caesar's death, he first joined Antony in fighting the republican armies of Brutus

and Cassius,and then turned against Antony while he was staying with Queen Cleopatra of

Egypt, and defeated him at Actium. Egypt was annexed and Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide.

Octavian then had the loyalty of the army, whilst at the same time he had taken over Julius

Caesar's role of leader of the "Peoples" party. He now took on the title of Augustus and became Rome's first emperor. The month of August is named after him.

He was a dictator with velvet gloves and tried to heal the political divisions within Roman society. He kept the form of the Republic and shared his government with the Senate, the Senate keeping responsibility for the administration of many provinces.

He set himself up as the "Princeps" or "First Citizen" - a president rather than a monarch.

However, in order to give his regime constitutional legitimacy and pass the job down the family line, he traced his descent from a mythical Trojan hero, whose mother was the goddess Venus. He got Virgil, the poet laureate of the day, to glorify this mythical connection and his ancestors in an epic poem called the Aeneid.

Virgil produced a beautiful

epic, but then drew a will instructing his executors to destroy the poem. When Virgil died,

Octavian heard about this and countermanded the will. The Aeneid is one of the finest works of Roman literature.

Octavian blamed the fall of the Republic (from which he had benefitted) on a collapse of morality within Roman high society. So he did his utmost to uphold and promote the old Roman religion and restore traditional Roman values. This was not universally accepted. Another poet, Ovid, wrote:"Expedit esse deos, et ut expedit, esse putemus" (It is expedient that the gods exist, and as

it is expedient, so let us believe they exist).

Ovid wrote books with titles such as: "The

Loves", "The Art of Love" and "The Transformations". He was exiled to the frozen wastes of

the Danube by the Black Sea because of "carmen et error" - a poem and a mistake. The poem was probably "The Art of Love". No one quite knows what the "mistake" was, but the rumour was that the poet had seduced the emperor's daughter!

There is a fine statue of the young Octavian in the hall under the dome at Castle Howard.

Cavalry Action - Trajan's column

How the The Roman Emperors ran the Empire.

The Emperors generally preferred to keep the army on the frontiers and outside Italy, as there was always a danger of military coups and civil war, if the legions were too close to the capital. The emperors kept their military budget to a

minimum, and the entire frontier was patrolled probably by no more than 350,000 troops - divided more or less equally between regular troops (the legionaries) and auxiliaries.

Instead of having a central reserve, they kept three legions in

Britain - far more than was needed. If there was a war on the Eastern Frontier, say, all the legions could move eastwards, each replacing the next one, but the only garrison which would be depleted would be the one in Britain.

The Romans had no secret police. So, with the army on distant frontiers, the entire internal security of the Empire had to depend more on diplomacy than armed force.

The task of government was shared with the Senate, and

Italy remained tax free for a very long time.

The emperors

encouraged good governance reinforced by the impartial

administration of Roman law. They also built towns and cities which could take care of themselves.

The whole system depended on diplomacy and the consent of the governed.

The Ludovisi Battle Sarcophagus - Battle between Romans and Dacians (now in Romania). The deceased is the man seen on horseback waving his troops on.

How strong was the position of Emperor?

Octavian, like Julius Caesar, was the leader of the "populares" faction, and so had considerable democratic legitimacy. He enjoyed the support of the legions which were personally loyal to the "populares" cause and the Caesar family. He was also a highly educated aristocrat, and had personal connections with all the leading republican families. His position was therefore unchallengeable and he was able to reorganise the empire so as to give it a very sound and stable administration.

However, he would have realised that ultimately his power and the power of his successors rested with the army. As the republican constitution remained in place (even though much modified), he could not claim to rule by divine right like the Chinese "Son of Heaven" on the other side of the world. In theory every power that was given to him had to be ratified by the Senate and the Roman People. It must have occurred to him that his successors could themselves fall to military coups, and that if different legions supported different candidates, there would be a return to civil war.

He tried to counter this by having an elite presidential guard at Rome (the Praetorian Guard) who were totally loyal to his family, maintaining the free supply of corn to the people of Rome and by promoting his family's mythical divine descent from the goddess Venus.

HIs efforts were only partially successful. His dynasty lasted less than a hundred years. It was interrupted in AD41 when the Praetorian Guards murdered Caligula and made Claudius emperor in his place. Finally in 68 AD there was a full-scale military rebellion against Nero followed by a year long civil war between three contenders for the supreme office.

The Flavian dynasty which followed lasted only 25 years. After the murder of the last Flavian emperor, Domitian, the Senate appointed an elderly distinguished lawyer called Nerva. Nerva realised that he could never hold the empire together without the support of the army. So he adopted a military commander called Trajan as his deputy and heir. When Trajan became emperor, he adopted another soldier, Hadrian as his heir, and made him his deputy. Hadrian did the same for Marcus Antoninus and Marcus Antoninus did the same for Marcus Aurelius.

There was never any secret police, but at the highest levels of government, there was competition for office, and as the emperors had no permanent constitutional position, the weaker emperors felt insecure and used informers to investigate cases of real or imagined plots against their regime. This sometimes resulted in a reign of terror amongst high society at Rome, but this rarely affected provincial society or Italy outside Rome, and with the exception of 68AD, the "year of the three emperors", the empire enjoyed a period of security, prosperity and sound administration for the first 200 years after Octavian took over the empire.

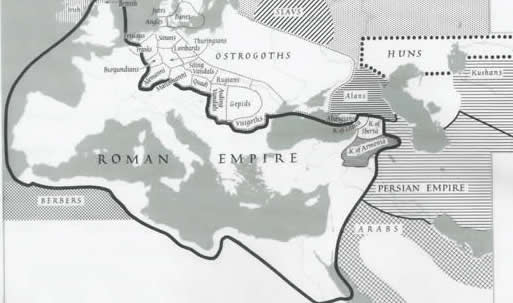

The Roman Empire 362 AD

Some Famous Emperors - some good: some bad.

Nero (Emperor 54-68 AD)

The last emperor of Octavian's dynasty. He became emperor at the age of 16, and for many years the administration was carried on by trusted and experienced ministers. Then he dismissed Seneca, his prime minister and became a cruel and brutal tyrant with a passion for self-advertisement, executing

or murdering anybody who seemed to be the slightest threat,

including Seneca.

Another writer murdered by Nero was Gaius Petronius. He was appointed as Nero's "judge of taste". He wrote a satyrical novel on the manners of the times, and this included a chapter where his principal characters gate crash on a dinner party provided by a millionaire freed slave called Trimalchio. As Trimalchio and his guests become progressively more drunk, they reveal more about themselves than perhaps they would have liked the others to know.

Trimalchio turns out to be a bore who cannot keep his attention on one subject for more than a few minutes, but impresses his guests with a rich variety of exotic dishes, which are served in time with singing waiters. He pretends to know all about Greek and Roman literature, and has a sound knowledge of astrology, but when he gets into Greek legends, he gets them hopelessly mixed up. He turns out to be a bisexual who got his freedom after satisfying the sexual gratification of both his former master and his former master's wife.

Nero was not a freed slave like Trimalchio, but scholars have always wondered if Nero saw something in Petronius' Trimalchio which might have been a take off of himself. Petronius was falsely accused of treason, and committed suicide. One wonders how far his charactarisation of Trimalchio had to do with this!

Nero fancied himself as an artist or musician. Rome caught fire

in 64AD and Nero was rumoured to have played the fiddle as

the city burned. He blamed the fire on Christians: some were thrown to the lions, others were smeared with pitch and

used as living torches to light the games he held by night in the imperial gardens.The victims included, according to tradition, St. Peter and St. Paul.

Eventually the armies revolted; Nero committed suicide and there was civil war between three rival contenders for the supreme office..

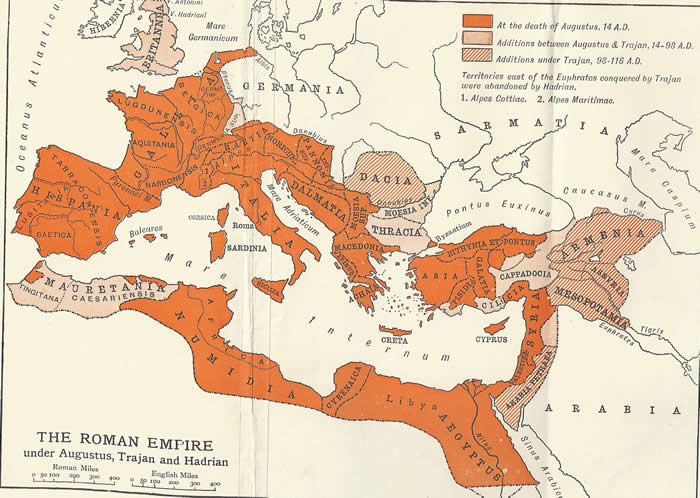

Trajan (Emperor 98 - 117 AD)

He was the last Roman emperor to embark on a long-term expansion of the Empire. He invaded Dacia (modern Romania) in 101 AD. The Roman occupation of this province lasted less than 200 years, but the Latin language caught hold and survived in spite of numerous invasions over the centruries. Daco-Romanian is the only modern Latin-based language which retains all three genders and nouns and adjectives which decline. Romany gypsies speak a language which is akin to Romanian.

His campaign started with the building of a bridge across the Danube. This took two years to build. This was an extraordinary achievement, bearing in mind the width of the river - more than a mile) and the technology available at the time. Could modern engineers bridge the Danube in two years?

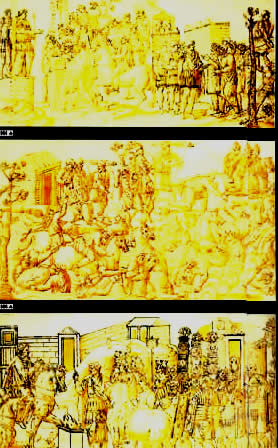

The sculptures on Trajan's Column in Rome record the story of his campaign in Dacia. The pictures give an idea of how the Roman army operated.

Trajan also embarked on an invasion of what we know as Iraq. However, Roman occupation was not permanent and was abandoned after Trajan's death.

Drawings of scenes from Trajan's Column showing two embassies of Dacians to Trajan, Dacian cavalry in difficulty crossing a river, and the emperor with his troops

Hadrian (Emperor 117-138AD)

Hadrian came from Spain. He was a man of extraordinary

versatility, a soldier, traveller, an able administrator, and a scholar devoted to literature, particularly Greek literature.

He toured the provinces and is well known for the monuments he built. These include Hadrian's Wall in Britain,

his tomb in Rome (now known as Castle St. Angelo), the Pantheon at Rome and a palace at Tivoli. He completed the

Temple of Olympian Zeus in Athens and built a library and other public buildings there.

Many of his buildings still stand, even if in ruins. The Pantheon (pictured below) is intact. It has survived because it was converted into a Christian church. the entrance was built in Octavian's time, but the round part with the dome was built by Hadrian. The interior is lit by a single hole at the apex of the dome, and the niches which now hold statues of Christian saints would originally have been occupied by statues of Pagan gods.

Inside and Outside the Pantheon

Marcus Aurelius (Emperor 161 - 180 AD)

This emperor was just as much at home with studying philosophy, as he was with his armies on the Northern frontier. He wrote a book on Stoic philosophy in Greek, which survives, but he spent much of his reign fighting defensive wars against brabarians on the Northern frontier.

His biggest mistake was not to make proper plans for his succession, with the result that he was succeeded by his son, Commodus. His character is beautifully portrayed in the film: "The Fall of the Roman Empire".

This bronze statue stands on the Piazza Del Campigoglio at Rome. It was restored by Michelangelo in 1538. It shows the emperor wearing civilian clothes, with the kind of beard which characterised Greek philosophers. However, he is riding a horse and his posture suggests he is at the head of his troops.

Commodus (Emperor 180 -193AD)

Commodus is the villain of the films "Fall of the Roman Empire" and "Gladiator".

For nearly a hundred years a tradition had grown up of emperors sharing power with a younger deputy who was himself an experienced army commander, and passing on power to the deputy on his death. Commodus was the son of Marcus Aurelius, the last such emperor. He had only three years experience in the army or in government and was quite unfit for office, but he took over on his father's death, at the age of 19.

Like Nero he started well, but then appointed his favourites as ministers. One of these, Cleander, would sell public offices to the highest bidder. Commodus' mistress Marcia virtually decided who to appoint as captain of the palace guards, and to other positions. In a fit of megalomania, Commodus had statues of himself set up all over the empire, showing him like Hercules with a club. He renamed all the months and the city of Rome

after himself.

There were plots against his life, and he became completely paranoid, executing anybody who seemed likely to threaten him, whether they were a threat or not.

He performed as a gladiator in the arena. Often, wounded soldiers and amputees would be placed in the arena for Commodus to slay with a sword. Commodus' eccentric behaviour would not stop there. Citizens of Rome missing their feet through accident or illness were taken to the arena, where they were tethered together for Commodus to club

to death while pretending they were giants.

Commodus was also known for fighting exotic animals in the arena, often to the horror of

the Roman people. According to one author, Commodus once killed 100 lions in a single

day. Later, he decapitated a running ostrich with a specially designed dart and afterwards

carried the bleeding head of the dead bird and his sword over to the section where the Senators sat and gesticulated as though they were next.

On another occasion, Commodus

killed three elephants on the floor of the arena by himself. Finally, Commodus killed a giraffe which was considered to be a strange and helpless beast.

Unlike in the films, Commodus did not die in the arena or in a duel in the Forum. His mistress, Marcia, fell out of favour. So she and the captain of the guards hired a professional athlete to strangle Commodus in his bath - before he could murder them.

True to form what was left of the government then put the office of emperor up for public auction. The millionaire who won the auction did not last long, and eventually the empire plunged into civil war, and there was a long period of instability. The empire survived this crisis, but was never quite the same again.

The Colosseum at Rome - Scene of Commodus" appearances in the arena

Click here to return to Roman civilisation menu

Click here for main Classics menu

If you have enjoyed reading these notes, please click hereand visit this site for info on Paul andrews' novel, the Loner.

|